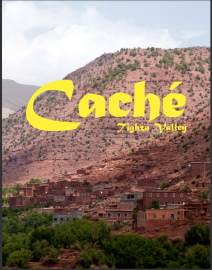

For my senior professional project, I wanted to combine hands-on journalism with my French language studies. So, I chose to spend five weeks in Morocco to compile interviews and observations in order to produce my final product, Caché. My friend, Kim Hackman (pictured below), a photojournalism student, served as my photographer throughout the trip.

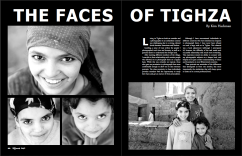

Because ethnographic and immersion journalism place the greatest importance on understanding the lives and cultures of others, I chose this method to research the Tighza Valley and the people who inhabit the region. By immersing myself into the Tighza village life for a period of time, I now have a better and understanding of the people and their traditions through in-depth interviews, conversations and observations. My stories, in the form of ethnographic and narrative journalism, attempt to place readers directly into the scene as the subject talks.

To provide a sense of the subjects’ lives, I interviewed approximately 55 villagers and had informal conversations with many others. The stories also capture events and daily life through observation. While in the village, we attended wedding ceremonies, watched women bake bread, went to a Ramadan feast and hiked four hours uphill to camp by Lake Tamda and talk to shepherds. We were also able to observe social gatherings and the villagers’ daily lives.

By attending social events as an observer, I had the ability to see life from an insider’s perspective but without altering the event. Because I did not speak the language, Tachelhit (tesh-la-heet), it was impossible to know everything happening at social events, or even in everyday dialogue. So, I gathered much of my background information through interviews and unstructured coversations with interpreters or with villagers (with the help of interpreters).

Throughout my time in Tighza, I conducted interviews in French, which my three interpreters then translated into Tachelhit. The interpreters, all of whom were born in the village, spoke Tachelhit, Arabic, and varying degrees of French. I worked closest with Mina El Mouden (pictured below), a 24-year-old woman with a strong academic background and a proficiency in French. El Mouden interpreted for a majority of the interviews, including all interviews with female villagers. Because of El Mouden’s gender and the lack of men present in the rooms where I interviewed, the women shared more openly about their stories and daily struggles. The most powerful stories came from the lives of women, who seemed empowered that someone would take an interest in them and listen to them.

When in Tighza, I stayed at the home of Carolyn Logan (pictured below), originally from the United Kingdom, and her husband, Mohamed El Qasemy, who was born and raised in the village. Logan, the only English speaker in the village, was my primary source of contact because we could communicate without interpretation, and she was familiar with the culture and people of the region.

Throughout the process, I trusted Logan to provide insight and explanation of events and cultural differences because she had lived in the culture for five years, and she explained these things in a way a Westerner could understand. Her views of village life proved to be very similar to my own perspective because we were both foreigners.

The 29-year-old Mohamed and his 25-year-old brother, Ahmed, served as my other interpreters. Both left school in their pre-teen years, but because of their experience working alongside foreigners visiting the village, they picked up French. The brothers, sons of a respected village elder, were well known among the people of Tighza, giving us access to more sources and contacts.

Our purpose is to present an accurate account of the lives of the villagers, both through text and through photos. My hope with the magazine is that after reading the stories of the villagers of Tighza, readers will come away with a better understanding of their lives and the rich culture of the Berbers of the High Atlas Mountains.

Click HERE to see the digital version of the magazine!

(Sample pages are shown below.)